JBRA Assisted Reproduction 2013; 17 (2):84-88

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20130011

The impact of the embryo quality on the risk of multiple pregnancies

O impacto da qualidade embrionária no risco de gravidezes múltiplas

aFertility – Centro de Fertilização Assistida

Accredited Redlara center

Av. Brigadeiro Luis, 4545. São Paulo, SP – Brazil

Zip: 01401-002

bInstituto Sapientiae – Centro de Pesquisa e Educação em Reprodução Assistida

Rua Vieira Maciel, 62. São Paulo, SP – Brazil

Zip: 04203-040

ABSTRACT

Objective: To determine the chance of pregnancy and the risk of multiple pregnancies taking into account the number and quality of transferred embryos in patients > 36 y-old or ≤ 36 y-old.

Methods: This case control study included 1497 patients undergoing intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycles. Cycles were split into groups according to the number and quality of the transferred embryos on the third or fifth day of development. The pregnancy rate and multiple pregnancy rate were compared between the embryo quality groups in patients <36y-old or ≥ 36y-old.

Results: In patients <36y-old, for the day three embryo transfer, no significant difference was noted in the pregnancy rate when the groups were compared; however, the multiple pregnancy rate was increased by the transfer of an extra low-quality embryo (17.1% vs 28.2%, p=0.020). For day five embryo transfer, the transfer of an extra blastocyst significantly increased the pregnancy rate (36.0% vs 42.4%, p<0.001) and the multiple pregnancy rate (4.4% vs 16.9%, p<0.001). In older patients, no significant difference was noted in the pregnancy rate when the groups were compared; however, when an extra low-quality embryo was transferred, a significantly increased rate of multiple pregnancies was observed for day three (18.2% vs 26.4%, p=0.049) and day five embryo transfers (5.2% vs 16.1%, p<0.001).

Conclusions: The transfer of an extra low-quality embryo may increase the risk of a multiple pregnancy. In younger patients, the transfer of an extra low-quality blastocyst may also increase the chance of pregnancy.

Keywords: assisted reproduction; multiple pregnancy; embryo transfer; embryo quality; implantation.

RESUMO

Objetivo: determinar a chance de gravidez e o risco de gestações múltiplas tendo em conta o número ea qualidade dos embriões transferidos em pacientes > 36 anos ou ≤ 36 anos.

Métodos: estudo caso-controle incluiu 1497 pacientes submetidos a ciclos de injeção intracitoplasmática de espermatozóide (ICSI) .Os ciclos foram divididos de acordo com o número e a qualidade dos embriões transferidos no dia 3 ou 5. As taxas de gravidez e de múltiplos foram comparadas entre os grupos de embriões de qualidade em pacientes <36Y-velhos ou ≥ 36Y-velho.

Resultados: Em pacientes <36 anos, para a transferência do embrião de três dias, não foi observada diferença significativa na taxa de gravidez quando os grupos foram comparados, no entanto, a taxa de gravidez múltipla foi aumentada pela transferência de um embrião de baixa qualidade extra (17,1% vs 28,2%, p = 0,020). Para a transferência de embriões dia cinco, a transferência de um blastocisto adicional aumentou significativamente a taxa de gravidez (36,0% vs 42,4%, p <0,001) e a taxa de gravidez múltipla (4,4% vs 16,9%, p <0,001). Em pacientes mais velhas, não foi observada diferença significativa na taxa de gravidez quando os grupos foram comparados, no entanto, quando um embrião de baixa qualidade extra foi transferido, uma taxa significativamente maior de gestações múltiplas foi observada para o dia três (18,2% vs 26,4%, p = 0,049) e para o dia 5 (5,2% vs 16,1%, p <0,001).

Conclusões: A transferência de um embrião de baixa qualidade extra pode aumentar o risco de uma gravidez múltipla. Em pacientes mais jovens, a transferência de um blastocisto de baixa qualidade extra também pode aumentar a chance de gravidez.

Palavras-chave: reprodução assistida, gravidez múltipla, transferência de embriões, a qualidade do embrião; implantação.

INTRODUCTION

Infertility, defined as a failure to conceive after a year of regular unprotected intercourse, affects 8% to 16% of reproductive-aged couples (Stephen and Chandra 2006). Depending on the cause of infertility and patient characteristics, management options range from pharmacologic treatment to more advanced techniques, referred to as assisted reproductive technologies (ART). Over the past two decades, the use of ART has increased dramatically worldwide and has made pregnancy possible for many infertile couples.

An initial step in ART is controlled ovarian stimulation (COS), which allows the traditional practice of replacing more than one embryo at a time within the uterus to maximise pregnancy rates. In fact, ART has been associated with a 30-fold increase in multiple pregnancies, compared with the rate of spontaneous twin pregnancies (ACOG 2005).

Multiple pregnancies are associated with a broad range of negative consequences for both the mother and the foetuses. Maternal complications include increased risks of pregnancy-induced hypertension, pre-eclampsia, polyhydramnios, gestational diabetes, foetal malpresentation requiring Caesarean section, postpartum haemorrhage, and postpartum depression. Babies from multiple pregnancies are at significantly higher risks of early death, prematurity, and low birth weight, as well as mental and physical disabilities related to prematurity (Ontario 2006).

Increased pregnancy rates, which have been associated with recent advances in ART, coupled with concerns about maternal and perinatal morbidity related to multiple pregnancies have led to attempts to restrict the number of embryos transferred (Maheshwari et al. 2011). Indeed, the necessity to decrease assisted-reproduction-induced iatrogenic multiple pregnancies has become a health, economic, and legal issue in several countries (Adashi et al. 2003).

The most effective approach to minimise the risk of multiple pregnancies is a single embryo transfer (SET) of either the cleavage or blastocyst stage embryos. There are concerns, however, that replacing only one embryo can reduce success rates, especially when cleavage stage embryos are transferred.

The acceptance of SET depends on access to financial support for multiple cycles of ART. Increased availability of insurance coverage is associated with fewer embryos per transfer and a lower multiple pregnancy rate (Reynolds et al. 2003; Stillman et al. 2009). However, the availability of funding for ART is variable, with some countries enjoying public sector support whereas others rely on patients to pay for the treatment, either directly or indirectly through expensive private insurance schemes.

Aside from the financial support, the maternal age, embryo quality, and number of previous attempts play a role in the decision of the number of embryos to be transferred. The goal of the present study was to determine the chance of pregnancy and the risk of multiple pregnancies by taking into account the number and quality of transferred embryos in patients > 36 y-old or ≤ 36 y-old.

METHODS

Study Design

This retrospective observational study enrolled 1497 patients undergoing intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycles between January 2011 and December 2012. The cycles were split into groups according to the number and quality of the transferred embryos on the third day or fifth day of development: the high-quality group, in which one or two high-quality embryos were transferred, and the high-and-low-quality group, in which one high and one low-quality or two high and one low-quality embryos were transferred. The cycles were also divided according to age (<36y-old or ≥ 36y-old), and the pregnancy rate and multiple pregnancy rate were compared between the embryo quality groups in the two patient age sets. All cases of severe spermatogenic alteration, including frozen and surgically retrieved sperm, were excluded from the study.

A written informed consent was obtained in which patients agreed to share the outcomes of their own cycles for research purposes, and the study was approved by the local institutional review board.

Controlled ovarian stimulation & laboratory procedures

Controlled ovarian stimulation was achieved by pituitary blockage using a GnRH antagonist (Cetrotide, Serono, Geneva, Switzerland), and ovarian stimulation was performed using recombinant FSH (Gonal-F; Serono, Geneva, Switzerland).

Follicular growth was followed by a transvaginal ultrasound examination that started on day four of the gonadotropin administration. When adequate follicular growth and serum E2 levels were observed, recombinant hCG (Ovidrel; Serono, Geneva, Switzerland) was administered to trigger the final follicular maturation. Oocytes were collected 35 hours after hCG administration by transvaginal ultrasound ovum pick-up.

The recovered oocytes were assessed for their nuclear status, and those in metaphase II were submitted to ICSI following routine procedures (Palermo et al. 1997).

Embryo morphology evaluation

Embryo morphology was assessed at 16-18 h post-ICSI and on the mornings of days two, three and five of embryo development using an inverted Nikon Diaphot microscope (Eclipse TE 300; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) with a Hoffmann modulation contrast system under 400 X magnification.

For the cleavage stage morphology, the following parameters were recorded: the number of blastomeres, the percentage of fragmentation, the variation in blastomere symmetry, and the presence of multinucleation and defects in the zona pellucida and cytoplasm. High-quality cleavage stage embryos were defined as those having all of the following characteristics: 4 cells on day two or 8−10 cells on day three;<15% fragmentation; symmetric blastomeres; absence of multinucleation; colourless cytoplasm with moderate granulation and no inclusions; absence of perivitelline space granularity; and absence of zona pellucida dysmorphism. Embryos lacking any of the above characteristics were considered to be of low-quality.

For the blastocyst stage morphology, the following characteristics were recorded: the size and compactness of the ICM and the cohesiveness and number of TE cells. Briefly, embryos were given a numerical score from one to six on the basis of their degree of expansion and hatching status, as follows: 1, an early blastocyst with blastocoels that occupy less than half the volume of the embryos; 2, a blastocyst with a blastocoel that is greater than half the volume of the embryo; 3, a full blastocyst with a blastocoels completely filling the embryo; 4, an expanded blastocyst; 5, hatching blastocyst; and 6, a hatched blastocyst. For full blastocysts onward, the ICM was classified as follows: high-quality, tightly packed with many cells; and low-quality, loosely grouped with several cells or with few cells. The TE was classified as follows: high-quality, many cells forming a cohesive epithelium; and low-quality, few cells forming a loose epithelium or very few cells.

Statistical analyses

The pregnancy and multiple pregnancy rates were compared between the groups of patients in which exclusively high-quality or high-and-low-quality embryos were transferred for patients > 36 y-old or ≤ 36 y-old. Data expressed as percentages were compared using the Chi-squared or Fisher exact test only when the expected frequency was five or fewer.

When a significant difference was found between the groups, binary regression models were also performed to evaluate the influence of transferring an additional low-quality embryo on the chance of pregnancy or multiple pregnancy risk. The results of the logistic regression were presented as the odds ratio (OR), p value, and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results were considered to be significant at the 5% critical level (p< 0.05). Data analysis was carried out using the Minitab (version 14) Statistical Program.

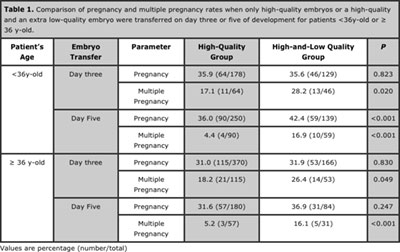

Table 1. Comparison of pregnancy and multiple pregnancy rates when only high-quality embryos or a high-quality and an extra low-quality embryo were transferred on day three or five of development for patients <36y-old or ≥ 36 y-old.

RESULTS

Of 1497 patients, 696 were< 36 y-old, out of which 428 had exclusively high-quality embryos transferred (the high-quality group) and 268 had an extra low-quality embryo transferred (the high-and-low-quality group). Eight hundred and one patients were ≥36y-old, out of which 550 had exclusively high-quality embryos transferred and 251 had an extra low-quality embryo transferred.

Patients <36y-old

In patients <36y-old, when embryo transfer was performed on the third day of development, no significant difference was noted in the pregnancy rate when the groups were compared (35.9% vs 35.6%for the high-quality groups and the high-and-low-quality groups, respectively, p=0.823, Table 1). However, the multiple pregnancy rate was increased by the transfer of an extra low-quality embryo (17.1% vs 28.2%for the high-quality and high-and-low-quality groups, respectively, p=0.020, Table 1). This finding was confirmed using a binary logistic regression, which showed that the transfer of an extra low-quality embryo was a determinant of the multiple pregnancy chance (OR = 1.53; CI 95% = 1.31–2.03; p= 0.020).

When embryo transfer was performed on the fifth day of development, the transfer of an extra blastocyst significantly increased the pregnancy rate (36.0% vs 42.4%for the high-quality and high-and-low-quality groups, respectively, p<0.001, Table 1). The logistic regression confirmed this finding, demonstrating that an extra blastocyst transfer is determinant of the pregnancy chance (OR = 1.50; IC 95% = 1.12–2.01;p<0.001).

The multiple pregnancy rates also differed among the groups (4.4% vs 16.9%for the high-quality and high-and-low-quality groups, respectively, p<0.001, Table 1). This result was also confirmed by the logistic regression model, which demonstrated a more than two-fold increase in the multiple pregnancy risk when an extra low-quality blastocyst was transferred (OR = 2.37; IC 95% = 1.40–4.02;p<0.001).

Patients ≥ 36 y-old

In older patients, when the embryo transfer was performed on the third day of development, no significant difference was noted in the pregnancy rates when the groups were compared (31.0% vs 31.9%for the high-quality and high-and-low-quality groups, respectively, p=0.830, Table 1), However, when an extra low-quality embryo was transferred, a significantly increased rate of multiple pregnancies was observed (18.2% vs 26.4%for the high-quality and high-and-low-quality groups, respectively, p=0.049, Table 1). This finding was confirmed using a binary logistic regression, showing that the transfer of an extra low-quality embryo was a determinant of the multiple pregnancy risk (OR = 1.58; CI 95% = 1.34–2.01; P = 0.044).

When embryo transfer was performed on the fifth day of development, no significant difference in the pregnancy rate was found based on whether exclusively high-quality blastocysts were transferred or one extra low-quality blastocyst was transferred (31.6% vs 36.9%for the high-quality and high-and-low-quality groups, respectively, p= 0.247). However, the multiple pregnancy rate was significantly increased by an extra low-quality blastocyst transfer (5.2% vs 16.1%for the high-quality and high-and-low-quality groups, respectively, p<0.001). This result was also confirmed by the logistic regression model, which demonstrated a three-fold increase in the multiple pregnancy risk when an extra low-quality blastocyst was transferred (OR = 3.12; IC 95% = 1.63–5.99;p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

Although most professional societies have issued guidelines to decrease the number of embryos to be transferred during assisted reproduction techniques, the incidence of multiple pregnancies remains unacceptably high (Pennings 2000).Therefore, there is a clear trend towards reducing the proportion of multiple pregnancies when possible. Currently, the best available strategy for preventing multiple births is to limit the number of transferred embryos.

In fact, as suggested by Olivennes and Frydman (1998), reducing the number of transferred embryos will also promote less intense stimulation protocols: a more `friendly IVF′. However, the poor implantation rate of in vitro fertilisation (IVF)-produced embryos encourages multiple embryo transfer to increase pregnancy rates.

Elective SET with the promise of the subsequent transfer of frozen–thawed embryos would achieve the goal of a single healthy child as a result of IVF treatment (Olivennes 2000). However, the success of the elective SET depends on the patient’s age and the quality of the transferred embryo.

The present study evaluated the chance of pregnancy and the risk of multiple pregnancies, taking into account the number and quality of transferred embryos in two patient age sets (> 36 y-old or ≤ 36 y-old). Our results demonstrated that for cleavage-stage embryo transfers, the pregnancy rate is the same if an extra low-quality embryo is transferred, compared to cycles in which exclusively one or two high-quality embryos are transferred for both patient age groups. The risk of multiple pregnancies, however, is significantly higher with an extra low-quality embryo transfer.

For blastocyst embryo transfer, the risk of multiple pregnancies is more than two-fold higher when an extra low-quality blastocyst is transferred for both patient age groups. However, in younger patients, the chance of pregnancy is also increased by an extra low-quality blastocyst transfer. In contrast, in older patients, the pregnancy rate is not increased by the transfer of an extra low-quality blastocyst.

Our findings demonstrated that the transfer of an extra low-quality embryo may not favour older patients either when cleavage-stage or blastocyst-stage embryos are transferred. In these patients, not only is the chance of pregnancy not increased but the rate of multiple pregnancies is also higher. This result suggests that the implantation potential may not considerably vary among embryos of the same cohort; in other words, when a high-quality embryo does not implant, the implantation chance of a low-quality embryo from the same cohort is low. However, when a high-quality embryo is able to implant, the implantation chance of another embryo of the same cohort may be higher.

It has been demonstrated that there is a decline not only in the oocyte quantity but also in the oocyte quality in older women (te Velde and Pearson 2002). In fact, older women present a reduction in follicular diameter compared to younger women, suggesting that larger follicles are generally recruited in the beginning of reproductive life; as women get older, the remaining follicles show a decrease not only in diameter but also in quality (Westergaard et al. 2007).

In younger patients, the transfer of an extra blastocyst, even if it is a low-quality blastocyst, is able to increase the pregnancy rate. Extended embryo culture and the subsequent transfer of blastocyst-stage embryos are associated with increased implantation rates (Blake et al. 2007; Papanikolaou et al. 2008). Prolonging the culture period allows for a better selection of embryos with a higher implantation potential and a better synchronisation between the endometrium and the embryo. However, although the pregnancy rate is increased, the risk of multiple pregnancies is also significantly higher when an extra embryo is transferred.

The decision about the number of embryos to be transferred lies with the physician and the patient. Although there currently appears to be sufficient evidence in the literature to suggest that elective SET may eliminate multiple pregnancies without compromising the cumulative live birth rate per couple, many clinicians are reluctant to adopt SET. Reports of low pregnancy rates when only one embryo is transferred (Ludwig et al. 2000)are responsible for the feeling of negativity regarding single embryo transfers.

Many potential parents may actually desire multiple pregnancies. In a previously published survey, only half of the couples had any objection to triplets and 20% deemed quadruplets acceptable (Gleicher et al. 1995). However, whether these couples are aware of the complications of multiple gestations is a matter of debate.

In a previous report by our group that investigated ART professionals’ attitudes towards their own IVF cycles, we showed that the transfer of a higher number of embryos and the associated multiple pregnancy risks were seen as acceptable, illustrating that when faced with infertility and ART, ART professionals have similar attitudes and perceptions to those of the infertile community. This finding suggests that the emotional aspects of the desire for a child and of the decision-making process related to ART have more influence over individuals than the intellectual knowledge about the risks and benefits of ART techniques(Bonetti et al. 2008).

CONCLUSION

Our results demonstrated that the transfer of an extra low-quality embryo may significantly increase the risk of a multiple pregnancy. In younger patients, the transfer of an extra low-quality blastocyst may also increase the chance of pregnancy; however, our findings raise the question of whether is it worth trying to increase the pregnancy rate to the detriment of a single pregnancy.

REFERENCES

ACOG. ACOG Committee Opinion #324: Perinatal risks associated with assisted reproductive technology. Obstet Gynecol 2005; 106(5 Pt 1): 1143-6.

Medline

Adashi, EY, Barri, PN, Berkowitz, R, Braude, P, Bryan, E, Carr, J, Cohen, J, Collins, J, Devroey, P, Frydman, R, Gardner, D, Germond, M, Gerris, J, Gianaroli, L, Hamberger, L, Howles, C, Jones, H, Jr., Lunenfeld, B, Pope, A, Reynolds, M, Rosenwaks, Z, Shieve, LA, Serour, GI, Shenfield, F, Templeton, A, van Steirteghem, A, Veeck, L and Wennerholm, UB. Infertility therapy-associated multiple pregnancies (births): an ongoing epidemic. Reprod Biomed Online 2003; 7(5): 515-42.

Medline Crossref

Blake, DA, Farquhar, CM, Johnson, N and Proctor, M. Cleavage stage versus blastocyst stage embryo transfer in assisted conception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; (4): CD002118.

Medline Crossref

Bonetti, TC, Melamed, RM, Braga, DP, Madaschi, C, Iaconelli, A, Jr., Pasqualotto, FF and Borges, E, Jr. Assisted reproduction professionals’ awareness and attitudes towards their own IVF cycles. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2008; 11(4): 254-8.

Medline Crossref

Gleicher, N, Campbell, DP, Chan, CL, Karande, V, Rao, R, Balin, M and Pratt, D. The desire for multiple births in couples with infertility problems contradicts present practice patterns. Hum Reprod 1995; 10(5): 1079-84.

Medline

Ludwig, M, Schopper, B, Katalinic, A, Sturm, R, Al-Hasani, S and Diedrich, K. Experience with the elective transfer of two embryos under the conditions of the german embryo protection law: results of a retrospective data analysis of 2573 transfer cycles. Hum Reprod 2000; 15(2): 319-24.

Medline Crossref

Maheshwari, A, Griffiths, S and Bhattacharya, S. Global variations in the uptake of single embryo transfer. Hum Reprod Update 2011; 17(1): 107-20.

Medline Crossref

Olivennes, F. Avoiding multiple pregnancies in ART. Double trouble: yes a twin pregnancy is an adverse outcome. Hum Reprod 2000; 15(8): 1663-5.

Medline Crossref

Olivennes, F and Frydman, R. Friendly IVF: the way of the future? Hum Reprod 1998; 13(5): 1121-4.

Medline Crossref

Ontario, HQ. In vitro fertilization and multiple pregnancies: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser 2006; 6(18): 1-63.

Medline

Palermo, GD, Colombero, LT and Rosenwaks, Z. The human sperm centrosome is responsible for normal syngamy and early embryonic development. Rev Reprod 1997; 2(1): 19-27.

Medline Crossref

Papanikolaou, EG, Kolibianakis, EM, Tournaye, H, Venetis, CA, Fatemi, H, Tarlatzis, B and Devroey, P. Live birth rates after transfer of equal number of blastocysts or cleavage-stage embryos in IVF. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod 2008; 23(1): 91-9.

Medline Crossref

Pennings, G. Avoiding multiple pregnancies in ART: multiple pregnancies: a test case for the moral quality of medically assisted reproduction. Hum Reprod 2000; 15(12): 2466-9.

Medline Crossref

Reynolds, MA, Schieve, LA, Jeng, G and Peterson, HB. Does insurance coverage decrease the risk for multiple births associated with assisted reproductive technology? Fertil Steril 2003; 80(1): 16-23.

Medline Crossref

Stephen, EH and Chandra, A. Declining estimates of infertility in the United States: 1982-2002. Fertil Steril 2006; 86(3): 516-23.

Medline Crossref

Stillman, RJ, Richter, KS, Banks, NK and Graham, JR. Elective single embryo transfer: a 6-year progressive implementation of 784 single blastocyst transfers and the influence of payment method on patient choice. Fertil Steril 2009; 92(6): 1895-906.

Medline Crossref

te Velde, ER and Pearson, PL. The variability of female reproductive ageing. Hum Reprod Update 2002; 8(2): 141-54.

Medline Crossref

Westergaard, CG, Byskov, AG and Andersen, CY. Morphometric characteristics of the primordial to primary follicle transition in the human ovary in relation to age. Hum Reprod 2007; 22(8): 2225-31.

Medline Crossref