JBRA Assisted Reproduction 2013; 17 (2):93-97

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20130013

The impact of the new 2010 World Health Organization criteria for semen analyses on the diagnostics of male infertility

O impacto dos novos critérios da OMS (2010) para avaliação seminal no diagnóstico da infertilidade

ªInstituto Valenciano de Infertilidad, Panamá City, Panamá.

ABSTRACT

Objective: To quantify the effect of the new 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) semen analysis reference values on reclassifying previous semen analysis parameters and definition of patients with male factor infertility.

Method: A uni-institutional retrospective chart review. Men who consulted for infertility during 2012 at Panamá IVI Clinic. The news 2010 WHO criteria were aplied to patients whose spermograms had been analyzed using the previous 1999 criteria, afterwards the reclassification was evaluated. Change or Reclassification were defined as the parameter being above the new reference values, previously being below that proposed by 1999 WHO.

Result(s): A total of 255 samples were analyzed, from which 67.5% were reclassified in at least one parameter and 113 (44%) were reclassified as normozoospermics. Using the 1999 WHO values there was a higher prevalence of abnormal findings specially of teratozoospermia that was 96%, while normozoospermia prevalence was 1.5%. With the 2010 values, these were 47% and 46% respectively. Also, with the criteria of 2010, a greater variety of diagnoses was evidenced.

125 patients (49%) were reclassified by morphology, 34 (13%) by motility, 19 (7.4%) by volume and 13 (5%) by sperm count; asthenozoospermia was the finding which showed the highest reclassification rate (69.3% ).

Conclusion(s): The new reference values resulted in many of our patients, who had had an abnormal spermogram, being reclassified as normozoospermics. This may lead to a different perspective on their diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: Andrology, spermogram, WHO criteria, infertility.

RESUMO

Objetivo: quantificar o efeito dos novos valores de referencia ( 2010) da Organização Mundial da Saúde (OMS) para a análise do sêmen, em reclassificar parâmetros de análise de sêmen anteriores e a definição de pacientes com infertilidade masculina.

Método: Estudo retrospectivo uni-institucional. Homens que consultaram para infertilidade ao longo de 2012 na Clínica IVI Panamá. Os novos criterios de 2010 da OMS foram aplicados aos pacientes cujos spermograms foram analisados usando os critérios anteriores (1999), e depois a reclassificação foi avaliada. Alterar ou Reclassificar foram definidos como sendo parâmetro acima dos novos valores de referência, previamente abaixo dos valores em 1999.

Resultados: Um total de 255 amostras foram analisadas, a partir das quais 67,5% foram reclassificadas em pelo menos um parâmetro e 113 (44%) foram reclassificadas como normozoospermicos. Usando as referências de 1999, houve uma maior prevalência de achados anormais especialmente de teratozoospermia que foi de 96%, enquanto a prevalencia de normozoospermia foi de 1,5%. Com os valores de 2010, estes eram 47% e 46%, respectivamente. Além disso, com os critérios de 2010, houve uma maior variedade de diagnósticos.125 pacientes (49%) foram reclassificados pela morfologia, 34 (13%) pela motilidade, 19 (7,4%) em volume e 13 (5%) na contagem de espermatozóides; asthenozoospermia foi o achado que apresentou a maior taxa de reclassificação (69,3%) .

Conclusão: Os novos valores de referência resultaram em muitos de nossos pacientes, que tiveram um espermograma anormal, sendo reclassificado como normozoospermicos. Isto pode levar a uma nova perspectiva do seu diagnóstico e tratamento.

Palavras-chave: Andrologia, espermograma, critérios da OMS.

INTRODUCTION

Clearly, the male and his semen quality is a key factor in investigating and addressing infertility. As evidenced by Brugh, et al., 2004, male infertility accounts for the infertility in almost 50% of couples.

Hence, the evaluation of the male partner is a crucial step in the diagnosis and treatment of couples attending an infertility first visit. Of course, we need a general medical history: anamnesis and physical examination, as in all fields of medicine, are prerequisites. However, in andrology, performing at least one semen analysis, ideally in a fertility center, is a mandatory step to establish the definitive fertility management for our couple.

Like many other diagnostic tests, the minimum “normal” reference values have been changing over time. While we can differentiate “normality” from “abnormality”, it is important to note that having a parameter below a minimum normal reference value does not necessarily mean being infertile, and males with values below these can still achieve pregnancies. At least two pathological spermograms, taken in a period of 15 days, is considered a requirement to definitively establish “abnormalities” in male fertility. Other authors (Mortimer et al., 1985, Castilla et al., 2006, Keel et al., 2006) recommend 3 or 4 analyses in a period of 3 months, representing one complete cycle of spermatogenesis.

The semen analysis should be performed by using standard techniques and criteria as described by the World Health Organization (WHO) and updated in 2002 by the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE). The reference values given by WHO are approximate, and, in theory, each laboratory should establish its own, but this task is almost impossible because of the difficulty in defining and obtaining a reference fertile population. For this reason, most laboratories adopted WHO criteria which come from a large fertile population, but do not, in themselves, confirm fertility or infertility.

Since 1987, WHO has published five editions of: “WHO Manual for the Examination of Human Semen and Sperm-Cervical Mucus Interaction.” The latest of 2010 used a fertile population in 14 countries and decreased the normal minimum cutoffs of 1999 criteria. The main objective (Cooper et al., 2011) was to improve the incidence of misdiagnosis and thereby improve the clinical management of patients. Of course, using these parameters to definitively establish normality would be very risky: while WHO evaluated a large and varied population (all of them fertile) some biases can be found regarding population which might lie outside (underdiagnosed or overdiagnosed) the range used in 2010 WHO. A man should not be classified as fertile or infertile based only on the spermogram or semen analysis.

Recently, Murray et al., 2012, published a study to assess the impact of the new 2010 WHO criteria on spermograms, and interpreting and defining the change from the cutoffs of 1999 WHO. They found reclassification in seminal volume, sperm concentration, motility and morphology, of 7%, 9.2%, 18.4% and 15.7%, respectively, for patients with multiple semen samples, and 7.9%, 6.2%, 9.9%, and 19.3%, respectively, for patients with a single semen sample. Their study also showed that 15.1% of patients were reclassified on at least one parameter. (Let us remember that reclassification was defined as a semen parameter changing from being below the old reference value to being above the new reference value.)

As shown, the application of the current 2010 WHO criteria to the samples increases the incidence of normozoospermia principally because of morphology and sperm motility.

The objective of this study is to quantify at IVI Panama clinic the magnitude of change in the interpretation of spermograms when we apply the new criteria of 2010 WHO criteria, in comparison to the 1999 WHO criteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a review of all spermogram reports made during 2012 for patients consulting for infertility at IVI Panamá Clinic. All reports have data concerning motility, concentration, morphology and volume. First, we applied both 1999 and 2010 WHO reference values, establishing the respective diagnosis for each sample. We then analyzed the percentage of reclassification or change and also other issues such as the frequency of diagnoses and findings (isolated or associated) to each WHO interpretation, as well as the characteristics of the reclassification and the new evidence alike.

The minimum reference values of 2010 WHO applied are: volume of 1.5 ml, sperm concentration of 15 million/mL, motility of 32%, and 4% of normal morphology (Kruger criteria). On the other hand, the 1999 WHO parameters included: volume of 2.0 ml, concentration of 20 million/mL, motility of 50%, and 14% of morphology.

RESULTS

We reviewed the database for all spermogram samples analyzed during 2012 belonging to patients who consulted at the IVI Panama Clinic. In total 255 semen reports were found for that period.

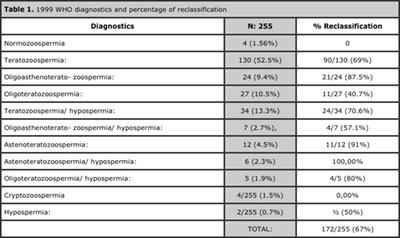

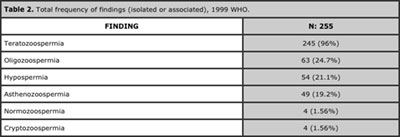

The most frequently found diagnostic applying the 1999 parameters was isolated teratozoospermia (52.5%), followed by teratozoospermia associated with hypospermia (13.3%). Normozoospermia frequency was 1.56%. The least frequent was isolated hypospermia (0.7%). See Table 1. Teratozoospermia (isolated or associated) was the finding which presented with the highest frequency (96%), followed by oligozoospermia, hypospermia, asthenozoospermia and finally cryptozoospermia. See Table 2.

67.5% of samples had reclassification in at least one parameter, with astenoteratozoospermia associated with hypospermia, being the diagnostic with the highest reclassification rate (100%). As we anticipated, normozoospermia and cryptozoospermia were the only diagnoses which were not reclassified. See Table 1.

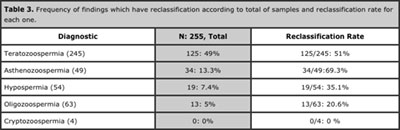

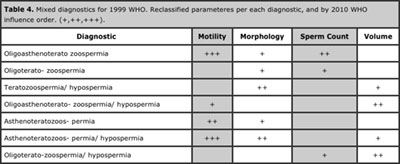

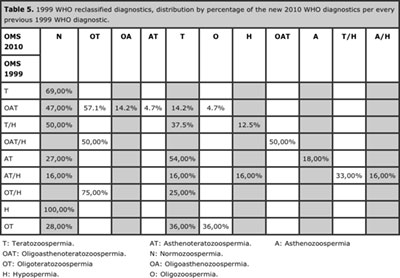

125 samples (49%) were reclassified by morphology, 34 (13%) by motility, 19 (7.4%) by volume and 13 (5%) by sperm count. Asthenozoospermia was the finding with the highest reclassification rate (69.3%). See Tables 3, 4 and 5.

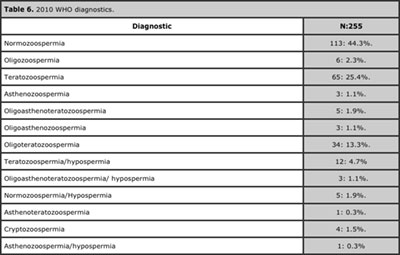

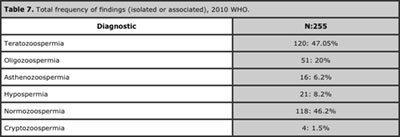

Applying the 2010 parameters, 113 patients (44%) went from having a spermogram abnormality to normozoospermic, which increased the total frequency of normozoospermia to 46.2% and diminished that of teratozoospermia (isolated or associated) to 47%. Furthermore, the diagnosis most frequently found was normozoospermia, while the least frequent was astenoteratozoospermia. Moreover, we observed the emergence of a variety of diagnostics which we did not see with 1999 criteria, such as isolated oligozoospermia, isolated asthenozoospermia, as well as the association of hypospermia with normozoospermia. Overall, with the 2010 parameters, we observed a higher frequency of normozoospermia, a lower prevalence of abnormalities, and a greater variety of diagnostics. See Tables 6 and 7.

Finally, keep in mind that 32.5% of the samples were not reclassified. From those, except normozoospermia (1.5%) and cryptozoospermia (1.5%), 29.5% continued to show the 1999 WHO abnormal findings, but with values closer to normal minimum cutoff of 2010 WHO.

Table 1. 1999 WHO diagnostics and percentage of reclassification

Table 2. Total frequency of findings (isolated or associated), 1999 WHO.

Table 3. Frequency of findings which have reclassification according to total of samples and reclassification rate for each one.

Table 4. Mixed diagnostics for 1999 WHO. Reclassified parameteres per each diagnostic, and by 2010 WHO influence order. (+,++,+++).

Table 5. 1999 WHO reclassified diagnostics, distribution by percentage of the new 2010 WHO diagnostics per every previous 1999 WHO diagnostic.

Table 6. 2010 WHO diagnostics.

Table 7. Total frequency of findings (isolated or associated), 2010 WHO.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

As mentioned, WHO has made changes to the spermogram parameters in the last few years. Some authors have previously suggested the need for change: Ombelet et al., 1997, showed a need for change in the interpretation of semen analysis, comparing fertile and sub-fertile population. Chia et al., 1998, applied the 1998 WHO parameters to spermograms in a fertile population, and showed that only 20% of fertile men had sperm morphology within normal parameters. It is said that the predictive power of the traditional reference values in semen parameters is not absolute and has a high degree of overlap between what is called normal and abnormal. Aziz et al., 2008, and Niederberger et al., 2011.

Murray and Cols argue that perhaps there is some bias in the 2010 WHO criteria, as some population might lie outside the range used in that (underdiagnosis or overdiagnosis), mainly because a spermogram does not have any upper limit, and on the other hand, it is difficult to diagnose a man as infertile, having a parameter below the reference value, when only fertile population was included in that study. Moreover, Jon et al., 2012, and Lamb et al., 2010, believe that some functional parameters which are not routinely evaluated in a spermogram can definitly influence the final diagnosis of fertility.

As we have seen, it is not easy to establish parameters of normality or abnormality on a diagnostic test that provides only one variable in relation to a desired goal (the pregnancy), and yet at the same time depends on subjective and sometimes non-standard measures prone to change.

How much the interpretation of a spermogram could change by applying the new 2010 WHO criteria has already been investigated by Murray et al. recently. They found that 15.1% of patients had reclassification in at least one parameter, mainly in morphology and motility; that between 15.7% and 19.3% of patients changed in morphology; and between 9.9% and 18.4% changed in motility. They defined their results as significant changes considering that the parameter variations due to the new 2010 WHO criteria were relatively small, being only: 5 million/mL in sperm concentration, 10% in morphology, 0.5 ml in volume, and 18% in progressive motility.

Our review showed findings even more surprising because when we applied 2010 parameters, we passed from a bleak panorama where normality practically didn’t exist using 1999 criteria: from a normozoospermia prevalence of 1.5% to a prevalence of 46.2%. This finding is more in line with what the literature has proposed, suggesting that around 50% of infertile couples present some degree of male factor. We also observed a large impact on the overall prevalence of teratozoospermia, which was 96% with 1999 criteria, but only 47% with 2010 criteria. So we can say that the new criteria have balanced the scales by rescuing spermograms finding normozoospermia, at the expense of a decrease mainly in the prevalence of teratozoospermia and asthenozoospermia.

Despite this, we hesitate to consider that we have the definitive version regarding the final diagnoses in male infertility, taking into account that some authors argue that nowadays some functional problems can be missed and be present in spermograms which are classified as normal, and instead we could be including patients with abnormalities in the normozoospermics group.

With This latter outcome many patients can lose the advantages of further evaluation, as Kolletis and Cols said. They have shown that up to 6% of men presenting with infertility may have serious medical problems which are subsequently discovered, within the context of good medical practice, during the investigation into the cause of their infertility.

The other issue that arises when applying this reclassification and adopting the 2010 WHO criteria is the therapeutic approach derived from that. Normally, the basic study of semen guides us towards the degree of complexity in assisted reproductive treatments that a couple requires, depending on the severity of the findings, and, of course, also depending on the other variables which play a role in achieving pregnancy.

Perhaps morphology is the most worrying parameter at the time of making a decision about what kind of treatment we should offer. While with the 2010 criteria, the cutoff for other parameters decreased by about a quarter in relation to the criteria of 1999, morphology decreased by two-thirds. In other words, the new 2010 criteria decreased the minimum normal cutoff in morphology to what was considered the limit for severe teratozoospermia in 1999. This type of change is a parallel discovery to some debates which arise about fertility treatments prognosis as well as indications of high or low complexity. Just to cite examples, some works argue that there is a significant decrease in the results, and others not, when performing artificial insemination with normal sperm morphology less than 4%. Lee et al., 2002, Van Waart et al., 2001, Matorras et al., 1995.

Thus, we have seen how complicated it is to define the cutoffs, as the treatment results vary from study to study, even after applying the new 2010 criteria. Moreover, many authors propose that semen parameters should not be classified as normal or abnormal, but as above or below the reference value. Perhaps, in terms of motility and concentration, we have a little less complication when indicating a treatment, taking into account the current availability of the test for sperm capacitation or motile sperm count (REM in Spanish), which nowadays establishes clear breakpoints about how the prognosis techniques changes significantly: above 3 million to offer low complexity treatments; above 1-1.5 million to offer conventional IVF; and below 1 million to offer ICSI.

Our study is a retrospective review that may have many limitations. The first and perhaps the most important is that we only analyzed patients with a single spermogram. Considering that within the current recommendations aimed at optimizing the study and interpretation of this test, and increasing diagnostic reliability, we should ideally recommend at least two spermograms per patient. However, it’s worth noting that the objective of this study was not to analyze the evolution over time of one or more patients, but to analyze with different reference values a single spermogram. On the other hand, in the study by Murray et al., 2012, which made a similar analysis to ours, we did not detect a significant difference in the reclassification among patients whether they had one or two spermograms.

The other limitation of this study is that we did not include reproductive outcomes and patients’ progress, especially from those who presented reclassification, in order to correlate and compare the probability of success in assisted reproduction treatments in relation to both 1999 and 2010 WHO criteria. In any case, we believe that this study could be the first step in examining the consequences of the new 2010 WHO criteria on male fertility diagnosis, and to start, if necessary, to redefine new reference values. As Cooper et al., authors of the new publication on WHO criteria, pointed out, it is clear that the semen and the current reference values, become a complementary tool to medical history, which is important to support our approach to, and management of, couples consulting for infertility, and working towards an optimization of their parameters. Also, with the appearance of new specific geographic region studies, further refinement of biases may avoid overlapping of normozoospermics with altered spermograms.

On our side, we feel that, with our simple study, we discovered a surprising change in reclassification of male infertility diagnoses by applying the new 2010 WHO criteria, and the next step might be to try to discover whether these changes are also reflected in the results of fertility treatments or in the natural conception. Clinical applications, and the predictive value of these changes, of course should be determined. Probably, reforms in diagnosis of male infertility and in approach are coming, reflected in a lower incidence of sperm abnormalities, and probably in a change in the andrological guidelines which influence the fertility treatments

REFERENCES

Aziz N, Agarwal A. Evaluation of sperm damage: beyond the World Health Organization criteria. Fertil Steril 2008;90:484–5.

Medline Crossref

Brugh VM, Lipshultz LI. Male factor infertility evaluation and management. Med Clin North Am 2004;88:367–85.

Medline Crossref

Castilla JA, Alvarez C, Aguilar J, Gonzalez – Varea C, Gonzalvo MC, Martinez L. Influence of analytical and biological variation on the clinical interpretation of seminal parameters. Hum Reprod. 2006; 21:847-51.

Medline Crossref

Chia SE, Tay SK, Lim ST. What constitutes a normal seminal analysis? Semen parameters of 243 fertile men. Hum Reprod 1998;13:3394–8.

Medline Crossref

Cooper TG, Noonan E, von Eckardstein S, Auger J, Baker HW, Behre HM, et al. World Health Organization reference values for human semen charac- teristics. Hum Reprod Update 2010;16:231–45. Niederberger CS. Semen and the curse of cutoffs. J Urol 2011;185:381–2.

Medline Crossref

De Jonge C. Semen analysis: looking for an upgrade in class. Fertil Steril 2012;97:260–6.

Medline Crossref

Jequier AM. Semen analysis: a new manual and its application to the under- standing of semen and its pathology. Asian J Androl 2010;12:11–3.

Medline Crossref

Keel BA. Within and between-subject variation in semen parameters in infertile men and normal semen donors. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:128-34.

Medline Crossref

Kolettis PN, Sabanegh ES. Significant medical pathology discovered during a male infertility evaluation. J Urol 2001;166:178–80.

Medline Crossref

Lamb DJ. Semen analysis in 21st century medicine: the need for sperm function testing. Asian J Androl 2010;12:64–70.

Medline Crossref

Lee RK, Hou JW, Ho HY, Hwu YM, Lin MH, Tsai YC, et al. Sperm morphology analysis using strict criteria as a prognostic factor in intrauterine insemination. Int J Androl. 2002; 25: 277-80.

Medline Crossref

Matorras R, Corcóstegui B, Pérez C, Mandiola M, Mendoza R, Rodriguez-Escudero FJ, et al. Sperm morphology analysis (strict criteria) in male infertility is not a prognostic factor in intrauterine insemination with husband’s sperm. Fertil Steril. 1995; 63:608 -11.

Medline

Murray KS, James A, McGeady JB, Reed ML, Kuang WW, Nangia AK. The effect of the new 2010 World ealth Organization criteria for semen analyses on male infertility Fertil Steril. 2012 Dec;98(6):1428-3.

Medline Crossref

Niederberger CS. Semen and the curse of cutoffs. J Urol 2011;185:381–2.

Medline Crossref

Ombelet W, Bosmans E, Janssen M, Cox A, Vlasselaer J, Gyselaers W, et al. Semen parameters in a fertile versus subfertile population: a need for change in the interpretation of semen testing. Hum Reprod 1997;12:987–93.

Medline Crossref

Van Waart J, Kruger TF, Lombard CJ, Ombelet W, et al. Predictive value of normal sperm morphology in intrauterine insemination (IUI): a structured literature review. Hum Reprod Update. 2001; 7 :495-500.

Medline Crossref