JBRA Assisted Reproduction 2015;19(1):16-20

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20150005

Demographic and obstetric outcomes of pregnancies conceived by assisted reproductive technology (ART) compared to non-ART pregnancies

1University of California, Irvine, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Orange, CA

2Miller Children’s Hospital – Long Beach Memorial Medical Center, Long Beach, CA

3Oakland University, William Beaumont School of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Rochester, MI

4Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Los Angeles, CA

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

No conflict of interest have been declared.

ABSTRACT

Objective: Use of assisted reproductive technology has increased steadily, yet multiple socioeconomic and demographic disparities remain between the general population and those with infertility. Additionally, both mothers and infants experience higher rates of adverse outcomes compared to their non-ART counterparts.

Methods: Using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) coding, we performed a retrospective review of all ART-conceived deliveries in California in 2009. A total of 551 ART pregnancies were compared to Non-ART pregnancies (n=406,885).

Results: The majority of ART deliveries belonged to women of advanced maternal age (AMA) and Caucasian or Asian race. Nearly half of all ART deliveries were multiple gestations. Compared to non-ART deliveries, ART pregnancies were associated with placenta previa, placental abruption, mild preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction. Conclusion: While not powered to detect all outcomes, our study highlights significant racial and ethnic disparities between ART and Non-ART pregnancies.

Keywords: ART pregnancy, IVF pregnancy, high-risk pregnancies.

INTRODUCTION

Assisted reproductive technology (ART) has grown steadily since the birth of the first U.S. infant conceived with this technology in 1981. In 2000, there were 25,228 live births and 35,025 infants as a result of ART reported to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (Wright et al., 2003); by 2010, this figure had nearly doubled to 47,090 live births and 61,564 infants (Sunderam et al., 2010).

There are several socio-demographic factors that impact who undergoes fertility treatment with ART. For instance, Caucasian women and women of advanced maternal age (AMA) are more likely to seek ART treatment. In addition, differences in race/ethnicity exist in terms of infertility prevalence; the National Survey of Family Growth demonstrated blacks as self-reporting a higher rate of infertility but, according to national delivery data represent only a small percentage of ART deliveries annually (Stephen & Chandra, 2006; Chandra et al., 2013). The cost of ART is also prohibitively high, potentially limiting women in lower socioeconomic strata access to ART (Chambers et al., 2009; Huddleston, et al., 2010). These factors can have significant impact on the availability of ART to certain socio-demographic groups.

Furthermore, ART pregnancies have significant health implications for mothers, as well as for their subsequent pregnancy. Nationally, 46% of ART pregnancies resulted in multiple-births compared to only 3% of spontaneously-conceived pregnancies (Sunderam et al., 2010). Infants conceived with this technology represented 20% of all multiple-birth infants in U.S. in 2009 (Sunderam et al., 2009). Among infants conceived with ART, a significantly higher proportion of pregnancies are complicated by low birthweight (<2500g), very low birthweight (<1500g), preterm birth (<37 weeks) and very preterm birth (<32 weeks) (Sunderam et al., 2010). Furthermore, ART and multi-fetal pregnancies demonstrate increased rates of adverse maternal outcomes, including higher rates of cesarean delivery, preeclampsia, abnormal placentation, cardiac morbidity, thromboembolism, postpartum hemorrhage, and pregnancy-related death (Sunderam et al., 2009; MacKay et al., 2006; ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice et al., 2005; Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 2012). Given these associations, ART pregnancies constitute a major healthcare concern.

In this study, we sought to identify and describe the socio-demographic characteristics of ART pregnancies delivered in 2009 using California discharge data. We also sought to identify pregnancy-related adverse outcomes associated with ART pregnancies in California.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This is a retrospective study using California health discharge data from 2009. The California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) provides a publicly available dataset comprising cases where a patient is treated in a licensed general acute care hospital in California (Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, 2012). It contains information regarding demographics, insurance type, diagnoses, specific procedures, and other data identified at time of discharge. The data has undergone a prior validation study and been used in several other obstetrical publications (Gilbert & Danielsen, 2003; Yasmeen et al., 2006; Schmitt et al., 2006; Fong et al., 2014). The University of California, Irvine institutional review board granted the study exempt from review because of the unidentified, retrospective design.

Of the 406,885 deliveries extracted from inpatient California discharge data using delivery codes, we identified 551 pregnancies conceived with assisted reproductive technology using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) coding for “pregnancy resulting from assisted reproductive technology” (V23.85). Other maternal conditions and procedures (e.g. diabetes, cardiac disease) were identified using ICD-9 coding as well. Procedures were also identified using ICD-9 procedure codes; for example, cesarean delivery was identified using procedure code 74.x (cesarean section and removal of fetus) in addition to diagnosis code 669.7x (cesarean delivery with all ART subjects (93.8%) had private insurance, compared 27.5-56.2). Higher-order multiples comprised nearly 1 of every 5 ART multiple gestations.

The study group of deliveries from pregnancies identified as being conceived by ART was compared to deliveries resulting from all remaining pregnancies (non-ART). We included only cases with full age and race/ethnicity information to minimize bias from omitted data in our logistic regression adjustments.

Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was used for calculation of continuous variables. Fisher’s exact or chi-square test was used for comparison between discrete variables. We performed a multivariable logistic regression analysis for adjustment of covariates, adjusting for the following factors: age, race, diabetes, cardiac disease, obesity, thyroid disease, chronic hypertension, and multiple gestations in order to try to establish an independent relation between ART and peripartum outcomes. Results were expressed in odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) was used for analysis.

RESULTS

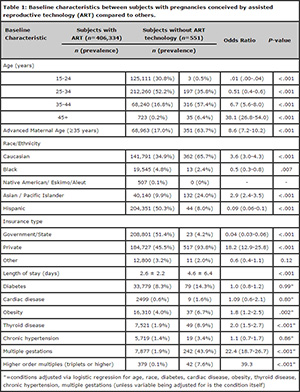

A total of 551 subjects whose pregnancies were conceived with ART were included in the study. These were then compared to all Non-ART pregnancies (n=406,885). Table 1 demonstrates the baseline characteristics between the two groups. Nearly two thirds (63.7%) of ART subjects were AMA, compared to only 17% of non-ART pregnancies. While only accounting for 0.2% of the entire study population, 6.4% of ART subjects were >45 years of age.

The majority of non-ART deliveries in California in 2009 were to Hispanic women (50.3%, n=204,351), yet they comprised only 8% of all ART pregnancies. Caucasians and Asians comprised most (90%) of ART subjects, a significant increase compared to the non-ART subgroup. Nearly all ART subjects (93.8%) had private insurance, compared to only 45.5% of non-ART subjects (OR 18.24, 95% CI 12.89 – 25.81).

Nearly half of all deliveries in the ART group were comprised of multiple gestations compared to the non-ART group (43.9% vs. 1.9%, OR 22.4, 95% CI 18.7-26.7). More than seven percent of ART pregnancies were comprised of higher-order multiples (triplets or more) compared to 0.1% of non-ART pregnancies (OR 39.3, 95% CI,27.5-56.2). Higher-order multiples comprised nearly 1 of every 5 ART multiple gestations.

Obesity and thyroid disease were much more prevalent in the ART group compared to the Non-ART group. No differences existed between the two groups regarding prevalence of diabetes, cardiac disease or chronic hypertension.

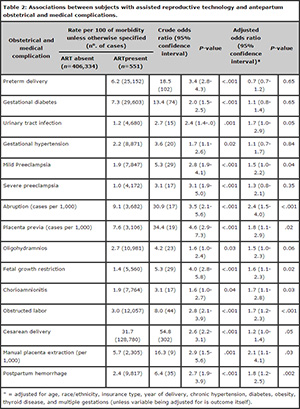

The obstetrical outcomes of pregnancies conceived with ART are demonstrated in Table 2. As compared to Non-ART deliveries, ART pregnancies were associated with several antepartum conditions, including urinary tract infection (adjusted OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.01-2.90), placenta previa (adjusted OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.10-2.85), placental abruption (adjusted OR 2.43, 95% CI 1.48-4.01), and mild preeclampsia (adjusted OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.01-2.19). There were also higher rates of fetal growth restriction (adjusted OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.07-2.32) and a trend towards oligohydramnios (adjusted OR 1.51, 95% CI 0.99-2.31).

More than half (54.8%, n=302) of ART pregnancies were delivered via cesarean section compared to only 31.7% of non-ART pregnancies (adjusted OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.00-1.43). Peripartum complications, such as obstructed labor (adjusted OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.22-2.29), manual placenta extraction (adjusted OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.50-5.63), and postpartum hemorrhage (adjusted OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.24-2.50) were all significantly more prevalent in ART deliveries.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics between subjects with pregnancies conceived by assisted reproductive technology (ART) compared to others.

Table 2. Associations between subjects with assisted reproductive technology and antepartum obstetrical and medical complications.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate several notable findings in regards to the socio-demographic composition of ART subjects. The majority of ART subjects in our dataset were of Caucasian or Asian race, while Hispanic and Black women represented only slightly more than 10% of subjects. This is consistent with other published national data that suggests a large racial disparity between the compositions of the populace receiving treatment for infertility versus the racial compositions among the general population (Luke et al., 2011). Prior studies have suggested that the live birth rate is lower among all minority groups undergoing ART (Luke et al., 2011; Seifer et al., 2008; Fujimoto et al., 2010). The largest series describing racial disparity in ART involved more than 80,000 subjects, and demonstrated a lower live birth rate among African Americans and Asians as compared to Caucasians and Hispanics (Feinberg et al., 2006).

One reason for such socio-demographic disparities may stem from racial/ethnic differences in access to fertility care. Although evidence suggests that blacks self-report lower fecundity rates, they may be less likely to utilize treatment with ART, possibly due to decreased access to it (Feinberg et al., 2006). The same holds true for Hispanics, many of whom also have limited access to ART, which is often provided via self-pay or private insurance. This is further compounded by the high costs of ART; in 2006, the cost per in vitro fertilization cycle ranged from $3,956 in Japan to $12,513 in the United States, with the United States having the highest rates internationally (Chambers et al., 2009).

In another study by Feinberg et al. that evaluated access to care among different races/ethnicities, African American women whom were given equal access to ART services utilized ART four-fold more relative to the general U.S. population. Despite increased access however, the live birth rate among African American women remained clinically lower than Caucasian women, although this was not found to be statistically significant (Feinberg et al., 2006).

As a result, the question remains whether the relative paucity of ART deliveries belonging to Hispanic or Black women was due to limited access to reproductive services or other unknown biomedical or socio-demographic factors.

A majority of ART subjects were of advanced maternal age, with a sizeable subset (6.3%) being >45 years of age. According to data from 2011 by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, nearly 70% of women in the United States who underwent ART were AMA (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention et al., 2013). This is consistent with our findings from California, in which 64% of our ART subgroup was AMA. Advanced maternal age is a well-established risk factor for numerous adverse outcomes, including preterm birth, small for gestational age infants, fetal and neonatal demise, increased cesarean delivery rates, preeclampsia, and postpartum hemorrhage (Waldenström et al., 2014; Barton et al., 2014).

Our data, however, was adjusted not only for age, but other factors including race/ethnicity, insurance type, multiple gestations, and medical comorbidities. This suggests that ART itself may independently be associated with the adverse obstetric outcomes identified. Several studies have demonstrated an increased risk for preterm birth, low birthweight, small for gestational age infants and cesarean delivery among ART-conceived pregnancies (D’Angelo et al., 2011; Merritt et al., 2014). Our results confirmed the risk of cesarean delivery and furthermore identified an association with preeclampsia, placental abruption, placenta previa, chorioamnionitis, obstructed labor, manual placental extraction and postpartum hemorrhage, findings which have been reflected elsewhere in the literature (Reddy et al., 2007).

In addition to the above findings, there are limitations of this study that deserve mention. Of the 406,885 included deliveries in California in 2009, only 551 were identified has having been conceived from ART. Given that California delivered the most ART-conceived pregnancies of any state in the country that year, the discrepancy in the number of ART deliveries compared to national data may be attributed to a failure to appropriately capture all ART deliveries that occurred. The capturing of an ART diagnosis by retrospective review of ICD-9 coding depends solely on the correct and complete diagnosis having been assigned at the time of patient discharge. The ICD-9 code for ART (V23.85) was first introduced in the year 2009, making it likely that not all hospital discharge coders were aware of its availability.

As a result of the small cohort, our study was likely not powered to detect differences in several outcomes; the association of preterm delivery with ART no longer remained statistically significant after adjustment for multiple gestations, age and other factors. Other, more rare outcomes associated with ART, such as fetal growth restriction and low birth weight, were not identified as statistically significant as well. These variations from the existing literature are likely explained by the inadequate sample size in our ART population.

Conversely, many of our study results reflect findings previously established in the literature, and shed light on new implications including associations with urinary tract infection, placenta previa, placental abruption, and mild preeclampsia. We performed an extensive adjustment of outcome variables, yet still identified several adverse outcomes associated with ART in a contemporaneous population. Furthermore, our data demonstrates how striking the socioeconomic disparity is between the ART population and the general population, suggesting that in terms of ability to obtain fertility care in the United States, there is far from equal access. These findings suggest that research is needed in several areas – why ART-related adverse outcomes occur and how to decrease them, and how to ensure that ART is available for all people who need it, regardless of racial or socioeconomic status.

REFERENCES

ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice, ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice, ACOG Committee on Genetics. ACOG Committee Opinion #324: Perinatal risks associated with assisted reproductive technology. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1143-6.

Medline

Barton JR, Sibai AJ, Istwan NB, Rhea DJ, Desch CN, Sibai BM. Spontaneously conceived pregnancy after 40: influence of age and obesity on outcome. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31:795-8.

Medline Crossref

Chambers GM, Sullivan EA, Ishihara O, Chapman MG, Adamson GD. The economic impact of assisted reproductive technology: a review of selected developed countries. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:2281-94.

Medline Crossref

Chandra A, Copen CE, Stephen EH. Infertility and impaired fecundity in the United States, 1982-2010: data from the National Survey of Family Growth. Natl Health Stat Report. 2013;67:1-18

Medline

D’Angelo DV, Whitehead N, Helms K, Barfield W, Ahluwalia IB. Birth outcomes of intended pregnancies among women who used assisted reproductive technology, ovulation stimulation, or no treatment. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:314-320.

Medline Crossref

Feinberg EC, Larsen FW, Catherino WH, Zhang J, Armstrong AY. Comparison of assisted reproductive technology utilization and outcomes between Caucasian and African American patients in an equal-access-to-care setting. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:888-94.

Medline Crossref

Fong A, Serra A, Herrero T, Pan D, Ogunyemi D. Pre-gestational versus gestational diabetes: a population based study on clinical and demographic differences. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28:29-34.

Medline Crossref

Fujimoto VY, Luke B, Brown MB, Jain T, Armstrong A, Grainger DA, Hornstein MD. Racial and ethnic disparities in assisted reproductive technology outcomes in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:382-90.

Medline Crossref

Gilbert WM, Danielsen B. Pregnancy outcomes associated with intrauterine growth restriction Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1596-9.

Medline Crossref

Huddleston HG, Cedars MI, Sohn SH, Giudice LC, Fujimoto VY. Racial and ethnic disparities in reproductive endocrinology and infertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:413-9.

Medline Crossref

Luke B, Brown MB, Stern JE, Missmer SA, Fujimoto VY, Leach R. Racial and ethnic disparities in assisted reproductive technology pregnancy and live birth rates within body mass index categories. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1661-6.

Medline Crossref

MacKay AP, Berg CJ, King JC, Duran C, Chang J. Pregnancy-related mortality among women with multifetal pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:563-8.

Medline Crossref

Merritt TA, Goldstein M, Philips R, Peverini R, Iwakoshi J, Rodriguez A, Oshiro B. Impact of ART on pregnancies in California: an analysis of maternity outcomes and insights into the added burden of neonatal intensive care. J Perinatol. 2014;34:345-50.

Medline Crossref

Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Multiple gestation associated with infertility therapy: an American Society for Reproductive Medicine Practice Committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:825-34.

Medline Crossref

Reddy UM, Wapner RJ, Rebar RW, Tasca RJ. Infertility, assisted reproductive technology, and adverse pregnancy outcomes: executive summary of a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:967-77.

Medline Crossref

Schmitt SK, Sneed L, Phibbs CS. Costs of newborn care in California: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:154-60.

Medline Crossref

Seifer DB, Frazier LM, Grainger DA. Disparity in assisted reproductive technologies outcomes in black women compared with white women Fertil Steril. 2008;90:1701-10.

Medline Crossref

Stephen EH, Chandra A. Declining estimates of infertility in the United States: 1982-2002. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:516-23.

Medline Crossref

Sunderam S, Chang J, Flowers L, Kulkarni A, Sentelle G, Jeng G, Macaluso M. Assisted reproductive technology surveillance--United States, 2006. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58:1-25.

Medline

Sunderam S, Kissin DM, Crawford S, Anderson JE, Folger SG, Jamieson DJ, Barfield WD. Assisted reproductive technology surveillance -- United States, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62:1-24.

Medline

Waldenström U, Aasheim V, Nilsen AB, Rasmussen S, Pettersson HJ, Schytt E. Adverse pregnancy outcomes related to advanced maternal age compared with smoking and being overweight. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:104-12.

Medline Crossref

Wright VC, Schieve LA, Reynolds MA, Jeng G. Assisted reproductive technology surveillance--United States, 2000. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2003;52:1-16.

Medline

Yasmeen S, Romano PS, Schembri ME, Keyzer JM, Gilbert WM. Accuracy of obstetric diagnoses and procedures in hospital discharge data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:992-1001.

Medline Crossref