JBRA Assisted Reproduction

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20130057

A survey on public opinion regarding financial incentives for oocyte donation in Brazil

1 Centre for Human Reproduction Prof. Franco Jr

Accredited Redlara center

2 Paulista Center for Diagnosis Research and Training, Research, Ribeirao Preto, Brazil.

3 Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics Botucatu Medical School, São Paulo State University - UNESP,

Research, Ribeirao Preto, Brazil.

RESUMO

Objetivo: avaliar opiniões na população brasileira sobre incentivos para a doação de óvulos.

Métodos: a abordagem descritiva transversal foi usada para consultar o público brasileiro. A coleta de dados envolveu o uso de um questionário estruturado sobre as questões legais e éticas que cercam a doação de óvulos. Os indivíduos foram selecionados aleatoriamente a aprtir da população em geral, utilizando diferentes listas de e-mail. Os potenciais participantes foram contactados por e-mail e convidados a participar do estudo através do preenchimento de um questionário na web, online.

Resultados: um total de 1565 pessoas completaram o estudo, incluindo 1284 mulheres (82%) e 281 homens (18%).Entre os entrevistadois, 1309 (83.6%) eram graduados universitários, 1033 (66%) tinha,m uma renda pessoal ≥1250 dólares/mês, 1346 (86%)se consideravam religiosos e 518 (33,1%) eram profissionais de saúde.Embora muitos participantes considerassem que as mulheres podem doar seus óvulos por razões altruistas, a maioria acredita que a falta de doações de óvulos é devida à proibição de pagamentos (64,3%) e que os incentivos facilitariam a decisão de doar oócitos (84,7%). A maioria dos participantes (65,3%) concordou que um incentivo financeiro ( ou seja, pagando a doadora) seria a solução mais prática para aumentar o número de doações de óvulos.Estes resultados tendem a ser independentes de sexo, idade, renda, religião, nível de escolaridade e profissão.

Conclusões: embora o Conselho Federal de Medicina proíba pagamentos para a doação de óvulos, a maioria dos participantes do estudo não teve objeção a compensação para doadoras de óvulos.Além disso, a maioria dos participantes concordou que um incentivo finaceiro é a solução mais prática para aumentar o número de doações de óvulos.

Palavras-chave: doação de óvulos;pesquisa; FIV; ética; opinião pública.

ABSTRACT

Objective: The objective of this study was to assess the opinions of the Brazilian population about incentives for oocyte donation.

Methods: A cross-sectional descriptive approach was used to consult the Brazilian public. The data collection involved the use of a structured questionnaire about legal and ethical issues surrounding oocyte donation. Individuals were randomly selected from the general population using different e-mail lists. Potential participants were contacted by e-mail and invited to participate in the study by completing an online web survey.

Results: A total of 1,565 people completed the survey, including 1,284 women(82%) and 281 men(18%). Among the respondents, 1,309(83.6%) were university graduates, 1,033(66%) had a personal income ≥1,250 US dollars/month, 1,346(86%) considered themselves to be religious and 518 (33.1%) were health professionals. While many participants believed that women may donate their oocytes for altruistic reasons, the majority believed that a lack of oocyte donations is due to the prohibition of payments(64.3%) and that incentives would facilitate the decision to donate oocytes(84.7%). The majority of the participants(65.3%) agreed that a financial incentive(i.e., paying the donor) would be the most practical solution for increasing the number of oocyte donations. These results tended to be independent of gender, age, income, religion, education level and profession.

Conclusion: While the Brazilian Federal Council of Medicine prohibits payments for oocyte donation, the majority of study participants had no objection to compensating oocyte donors. Moreover, most of the participants agreed that a financial incentive is the most practical solution to increasing the number of oocyte donations.

Keywords: Oocyte donation, Survey, IVF, Ethics, Public opinion.

INTRODUCTION

With the development of in vitro fertilization (IVF) techniques (Edwards et al., 1980), a wide range of new therapeutic possibilities have become available, including the use of donated oocytes. Oocyte donation (OD) is a treatment option for women with hypergonadotropic hypogonadism; women of advanced reproductive age; women with diminished ovarian reserves; women who are affected by, are carriers of or have a family history of a significant genetic defect; women with poor oocyte and/or embryo quality; or women who have had multiple previous failed attempts to conceive via assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) (ASRM, 2013). Since the first successful use of donated oocytes (Lutjen et al., 1984), OD has become a common and routine procedure that gives satisfactory pregnancy and take-home baby rates (Murray & Golombok, 2000; Isikoglu et al., 2006; Pennings, 2007; Purewal & Akker, 2009; CDC, 2012; de Mouzon et al., 2012; ASRM, 2013; Zegers-Hochschild et al., 2012). Consequently, the global demand for oocytes has been increasing, and more couples are willing to use oocyte donation as a way to overcome infertility. However, the number of donors is often insufficient relative to oocyte demand.

The Brazilian Federal Council of Medicine (2011), which regulates medical practice in Brazil, has mandated that gamete donation will never have a profitable or commercial nature and that donors should not know the identity of the recipient (and vice versa). Similarly, the National Agency for Sanitary Vigilance (2011) has mandated that germ cell and tissue donations must be anonymous and that donors cannot be compensated. Thus, although oocyte donation involves unpleasant and intrusive procedures that are associated with some risks, the current policy in Brazil is to consider gamete donation as an anonymous/altruistic process only; offering payments and incentives to donors is forbidden. This decision may jeopardize the supply of oocyte donors. In fact, licensed clinics have encountered increasing difficulties in recruitment. However, there are no data on the attitudes of the Brazilian people regarding oocyte donation.

Considering that one of the first steps in the creation or modification of regulations is to determine the current perspectives of society, this study aimed to assess the opinion of the Brazilian population about incentives for oocyte donation.

METHODS

A cross-sectional descriptive approach was used to survey the Brazilian public between October and November 2012. Individuals were randomly selected from the general population using different e-mail lists. Potential participants were contacted by e-mail and invited to participate in the study by completing an online web survey. There were no restrictions on the population selection and no incentives for completing the survey.

The data collection involved a structured questionnaire about the legal and ethical issues surrounding oocyte donation. The questionnaire was comprised of one part with nine questions that permitted only one choice (yes or no) for each response. An Internet-based system prevented double responses.

The data are reported as percentages. The Chi-squared test was used when appropriate. The level of significance was set at P<0.05.

RESULTS

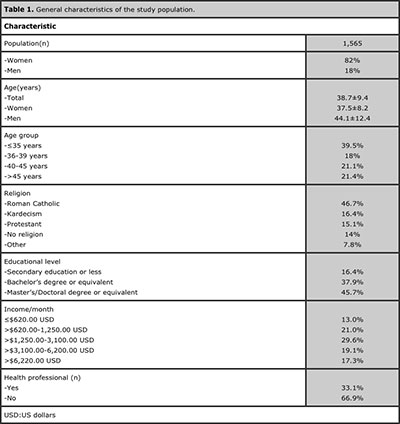

A total of 1,565 people completed the survey, including 1,284 women (82%, age: 37.5±8.2 years) and 281 men (18%, age: 44.1±12.4 years). Among the respondents, 1,309 (83.6%) were university graduates, 1,033 (66%) had a personal income of more or equal than $1,250.00 US dollars/month, 1,346 (86%) considered themselves to be religious and 518 (33.1%) were health professionals. The general characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

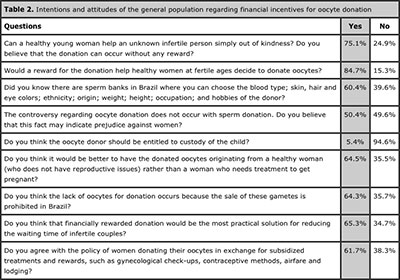

The general results showed that while many participants believed that women may donate their oocytes for altruistic reasons, the majority believed that a lack of oocyte donations is due to the prohibition of payments (64.3%) and that incentives would facilitate the decision to donate oocytes (84.7%). The majority of the participants (65.3%) agreed that a financial incentive (i.e., paying the donor) would be the most practical solution for increasing the number of oocyte donations. Table 2 summarizes these results.

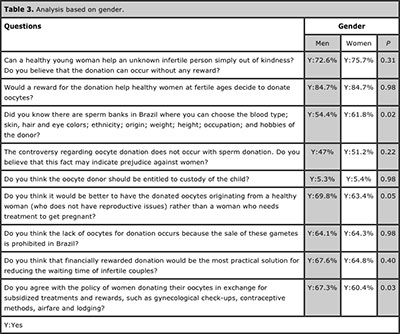

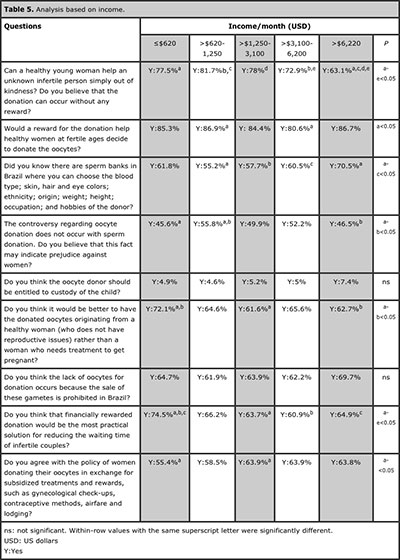

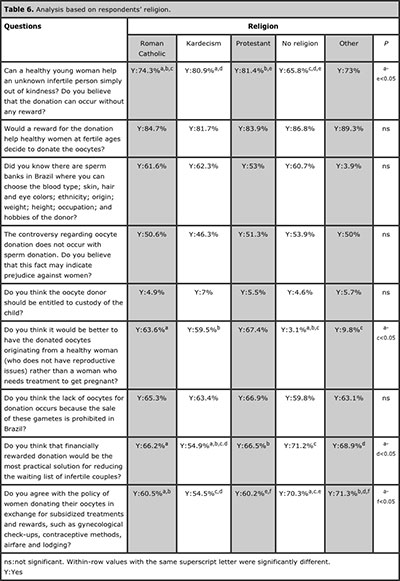

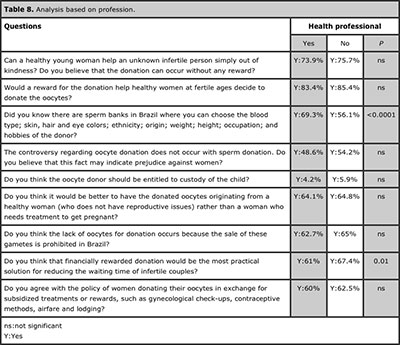

While there were slight group differences in the results, the responses among different subgroups of the population were relatively stable. The majority of the participants agreed that a financial incentive would be the most practical solution for increasing the number of oocyte donations; this finding was independent of gender (Table 3), age (Table 4), income (Table 5), religion (Table 6), education level (Table 7) and whether the respondent was a health professional (Table 8).

Table 1. General characteristics of the study population.

Table 2. Intentions and attitudes of the general population regarding financial incentives for oocyte donation

Table 3. Analysis based on gender.

Table 4. Analysis based on respondent age.

Table 5. Analysis based on income.

Table 6. Analysis based on respondents’ religion.

Table 7. Analysis based on respondents’ educational level.

Table 8. Analysis based on profession.

DISCUSSION

In addition to a couple’s preferences, the decision about which technique to use in infertility treatment is primarily a medical matter. However, assisted reproduction procedures are regulated through legislation and/or ethical standards. These standards are often based on a society’s socio-cultural and religious structures as well as their ethical and moral values. Legislation often prohibits or imposes limitations on certain reproductive treatments without the necessary opinions and education of the society. These restrictions can lead to reproductive tourism, when couples travel to countries with flexible legislation seeking treatments they are unable to receive in their country of residence (Hughes & DeJean, 2010; Lunt & Carrera, 2010; Crozier & Martin, 2012; de Mouzon et al., 2012; Inhorn et al., 2012; Shalev & Werner-Felmayer, 2012). Reproductive tourism is rare in Brazil but common in Europe and a profitable business in India. In general, the procedures of ART involving the use of so-called “third party” as a as sources of gametes or embryos or as gestational carriers are subject to regulation.

Oocyte donation involves unpleasant and invasive procedures that are associated with certain risks and thus require a substantial commitment on the part of the donor. These risks include complications with the drugs that are used to induce ovulation, complications with follicular aspiration and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome; potencial negative impact on future fertility and psychological damage (Bodri et al., 2008; Kramer et al., 2009; Bukulmez et al., 2010; Aragona et al., 2011; Stoop et al., 2012; Weinerman & Grifo, 2012; Alberta et al., 2013; Siristatidis et al., 2013). While OD is not prohibited in Brazil, the practice usually involves a long wait for the oocytes, which often exceeds one year. In 2010, the Latin American Registry (Zegers-Hochschild et al., 2012) showed that 51% of the total IVF/ICSI cycles were performed in Brazil but only 27% of the cycles involved oocyte donations. This finding demonstrates the technique’s low frequency of use. The possibility of offering some type of compensation, especially financial, could speed up the process. According to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM, 2013), monetary compensation for the egg donor should reflect the time, inconvenience, physical and emotional demands and risks associated with oocyte donation. The results of the present study challenge the paradigm of prohibiting compensation for oocyte donation. A significant majority of respondents approved more than simply compensating donors. In fact, they believed that the demand for oocytes would be better supplied if donors were financially compensated.

There is a diverse range of regulations in different countries. While oocyte donation is prohibited in some countries, other countries only impose restrictions on the method of obtaining oocytes (The Nordic Committee on Bioethics, 2006; Hughes & DeJean, 2010; Inhorn, 2010; Lunt & Carrera, 2010; Wang et al., 2010; Shalev & Werner-Felmayer, 2012). However, in countries as the USA and Spain, where financial compensation can be offered to oocyte donors, a large number of oocyte donation cycles has been recorded (Bergmann, 2011; CDC, 2012; de Mouzon et al., 2012; ASRM, 2013).

Oocyte donors are not a homogeneous group (Murray & Golombok, 2000; Purewal & van den Akker, 2009). One group of oocyte donors is comprised of donor patients who make agreements with infertility clinics involving the donation of part of their oocytes in exchanged for subsidized treatment. While supporters of oocyte sharing argue that this system is better than one that convinces women who do not need infertility treatment to assume the risks associated with donation (Murray & Golombok, 2000), this practice can be understood as offering financial compensation for oocyte donation. These oocytes often come from women from infertile couples, which can result in lower gamete quality. The majority of respondents in the present study thought that donated oocytes should come from healthy women rather than from women who require fertility treatment. In any case, this practice has no formal approval in Brazil (Brazilian Federal Council of Medicine, 2011).

The population of donors also consists of women who make donations to specific recipient couples. According to a systematic review of oocyte donation (Purewal & van den Akker, 2009), studies have reported that the majority of known donors are motivated to donate because of their personal relationship with the recipients, particularly if they are related. However, this practice is not possible in Brazil, as the anonymity of oocyte donation is mandatory. Furthermore, future interferences in the lives of the recipient couple, especially regarding the child’s education, are an important issue to consider.

Another group of donors are voluntary donors who donate their oocytes without financial compensation. These donors often cite altruistic motives as the reason for the donation, and the experience of infertility by their relatives or friends or in their own lives is not uncommon (Purewal & van den Akker, 2009). According to our survey, 75.1% of the participants believed that donations with no compensation should occur. The question is how to recruit these potential patients so that the demand for oocytes can be met, especially after the donation process and the associated risks are explained. Even considering the commercial nature, financial compensation is a logical option that meets the needs of oocyte clinics, obtains better quality oocytes and maintains anonymity.

Interestingly, the subgroups were consistent with their assessments, even in terms of religion. Although some religions historically disapprove the practice of assisted reproduction, such as Roman Catholics, the absolute majority of respondents approved the idea of financial compensation. In a similar study that directly reflected the public opinion, Isikoglu et al. (2006) analyzed the general attitudes of people toward various aspects of oocyte donation. The authors noted that less than half of the participants thought that their religion would prevent oocyte donation in cases of need.

The interpretation of the present study’s data should be in the context of the study limitations. The number of answers may be considered to be too small to be representative of the population’s opinion. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first evaluation of the opinion of the Brazilian population on this topic. At the very least, these results can be used as a foundation for more comprehensive studies. Additionally, other public surveys that evaluated human reproduction issues had smaller population samples than the present study (Westlander et al., 1998; Isikoglu et al., 2006; Khalili et al., 2008). In any case, future studies that obtain higher response rates and include underrepresented voices (i.e., more men, members of other religions and people with less education) would complement the present study. Another potential problem with the present study is selection bias. People who had an interest in fertility issues were more likely to respond to and participate in the study. Finally, the response rate of 31.3% is smaller than response rates in mail surveys. However, the response rate of this study is consistent with the average response rate that was reported in a meta-analysis of online surveys (Cook et al., 2000).

In conclusion, while the Brazilian Federal Council of Medicine (2011) prohibits rewarded oocyte donation, the majority of participants had no objection to compensating oocyte donors. Moreover, most participants agreed that a financial incentive (i.e., paying the donor) is the most practical solution for increasing the number of oocyte donations. Future studies that obtain higher response rates and include underrepresented voices would complement the results of the present study. The results of a wider public survey on oocyte donation may determine whether the best policies are in place and may determine future oocyte donation policies.

REFERENCES

Alberta HB, Berry RM, Levine AD. Compliance with donor age recommendations in oocyte donor recruitment advertisements in the USA. Reprod Biomed Online. 2013 in press.

Medline Crossref

Aragona C, Mohamed MA, Espinola MS, Linari A, Pecorini F, Micara G, Sbracia M. Clinical complications after transvaginal oocyte retrieval in 7,098 IVF cycles. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:293-4.

Medline Crossref

ASRM - American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Recommendations for gamete and embryo donation: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:47-62.

Medline Crossref

Bergmann S. Reproductive agency and projects: Germans searching for egg donation in Spain and the Czech Republic. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2011;23:600-8.

Medline Crossref

Bodri D, Guillen JJ, Polo, A, Trullenque M, Esteve C, Coll O. Complications related to ovarian stimulation and oocyte retrieval in 4052 oocyte donor cycles. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2008;17:237-43.

Medline Crossref

Bukulmez O, Li Q, Carr BR, Leander B, Doody KM, Doody KJ. Repetitive oocyte donation does not decrease serum anti-Mullerian hormone level. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:905-12.

Medline Crossref

Crozier GK, Martin D. How to address the ethics of reproductive travel to developing countries: a comparison of national self-sufficiency and regulated market approaches. Dev World Bioeth. 2012;12:45-54.

Medline Crossref

de Mouzon J, Goossens V, Bhattacharya S, Castilla JA, Ferraretti AP, Korsak V, Kupka M, Nygren KG, Andersen AN. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2007: results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:954-66.

Medline Crossref

Edwards RG, Steptoe PC, Purdy JM. Establishing full-term human pregnancies using cleaving embryos grown in vitro. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1980;87:737-56.

Medline Crossref

Hughes EG, DeJean D. Cross-border fertility services in North America: a survey of Canadian and American providers. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:e16-e19.

Medline Crossref

Inhorn MC, Patrizio P, Serour GI. Third-party reproductive assistance around the Mediterranean: comparing Sunni Egypt, Catholic Italy and multisectarian Lebanon. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010;21:848-53.

Medline Crossref

Inhorn MC, Shrivastav P, Patrizio P. Assisted reproductive technologies and fertility “tourism”: examples from global Dubai and the Ivy League. Med Anthropol. 2012;31:249-65.

Medline Crossref

Isikoglu M, Senol Y, Berkkanoglu M, Ozgur K, Donmez L, Stones-Abbasi A. Public opinion regarding oocyte donation in Turkey: first data from a secular population among the Islamic world. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:318-23.

Medline Crossref

Khalili MA, Isikoglu M, Tabibnejad N, Ahmadi M, Abed F, Parsanejad ME, Ghasemi M, el Jamal H. IVF staff attitudes towards oocyte donation: a multi-centric study from Iran and Turkey. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;17 Suppl 3:61-6.

Medline Crossref

Kramer W, Schneider J, Schultz N. US oocyte donors: a retrospective study of medical and psychologic issues. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:3144-9.

Medline Crossref

Lunt N, Carrera P. Medical tourism: assessing the evidence on treatment abroad. 2010;66:27-32.

Medline Crossref

Lutjen P, Trounson A, Leeton J, Findlay J, Wood C, Renou P. The establishment and maintenance of pregnancy using in vitro fertilisation and embryo donation in a patient with primary ovarian failure. Nature. 1984;307:174-5.

Medline Crossref

Murray C, Golombok S. Oocyte and semen donation: a survey of UK licensed centres. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:2133-9.

Medline Crossref

Pennings G. Mirror gametes donation. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;28:187-91.

Medline Crossref

Purewal S, van den Akker OBA. Systematic review of oocyte donation: investigating attitudes, motivations and experiences. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:499-515.

Medline Crossref

Shalev C, Werner-Felmayer G. Patterns of globalized reproduction: egg cells regulation in Israel and Austria. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2012;1:15.

Medline Crossref

Siristatidis C, Chrelias C, Alexiou A, Kassanos D. Clinical complications after transvaginal oocyte retrieval: a retrospective analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33:64-6.

Medline Crossref

Stoop D, Vercammen L, Polyzos NP, de Vos M, Nekkebroeck J, Devroey P. Effect of ovarian stimulation and oocyte retrieval on reproductive outcome in oocyte donors. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:1328-30.

Medline Crossref

Wang F, Sun Y, Kong H, Li J, Su Y, Guo Y. The evolution of oocyte donation in China. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010 Jul;110(1):53-6.

Medline Crossref

Weinerman R, Grifo J. Consequences of superovulation and ART procedures. Semin Reprod Med. 2012;30:77-83.

Medline Crossref

Westlander G, Janson PO, Tägnfors U, Bergh C. Attitudes of different groups of women in Sweden to oocyte donation and oocyte research. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1998;77:317-21.

Medline Crossref